C.W. Gross is the writer of the blog Voyages Extraordinaires: Scientific Romances in a Bygone Age and has recently published the anthologies Science Fiction of America's Gilded Age and Science Fiction of Antebellum America.

Jules Verne: A Literary Pilgrimage - Part Two

by C.W. Gross

The grand Cathédrale Notre-Dame d'Amiens overlooks a quaint town square. Photo © C.W. Gross.

Romanticism, of the unscientific kind, began largely as a reaction against the Rationalism of the Enlightenment and its subsequent revolutions, industrial and political. Humanity became a means to an end of industrial production, wealth generation, scientific dissection, and imperial expansion, rather than an end unto itself finding its fullness in God. The Enlightenment, for all its promises and proclamations, seemed only to lead to moral, economic, social, and spiritual destitution. In speaking of the German thinker Novalis, Pauline Kleingeld describes Romanticism's objections:

The early German romantics criticize the Enlightenment for failing to appreciate the most essential components of truly human life: love, emotional bonds, beauty, shared faith, and mutual trust. They claim that the Enlightenment emphasis on reason, abstract principles, and rights overlooks these crucial aspects of human existence... In their own way, they endorse many of the ideals of the Enlightenment, especially the ideals of individuality, freedom, anti-authoritarianism, and equality. But they accuse the Enlightenment of having degraded these very ideals to atomistic individualism, rootlessness, self-interestedness, and abstract legalism...

Romanticism looked mainly to the European Middle Ages as a spiritual, intellectual, nationalistic, and aesthetic model, but was also satisfied with any faraway times, exotic places, and indigenous cultures... Anything that would help counterbalance the deadening weight of the Enlightenment's dark age. Nature held a particular resonance for the Romantics, as the embodiment of wild, untempered, unfettered, and untamed emotional and creative processes, as well as for its own intrinsic spiritual and aesthetic value.

Early in his career, Jules Verne was well on the Romantic road trod by Dumas, Longfellow, Cooper, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Byron, or Shelly. However, Verne discovered something that would give shape to an entirely new genre of fiction. He realized that the solitary creative genius of Romanticism could be a man of science, and that technology could be the vehicle to a transcendental appreciation of nature. Reason need not be the enemy: it could be a tool to reach that which is beyond it.

Scientific Romances sought out the romance implicit to science, the poetic probing of the mysteries of Space, Time, Nature, and even Divinity. They are, in many ways, a hymn to the beauty, wonder, and majesty of Creation. That hymn includes an exultation in humanity and its varied, diverse, creative prowess. Verne's Scientific Romance denotes the combination of things: Science and Romance, stories of adventure with a flair of style, exotic exploration in civilized comfort, progress directed by tradition, moving into the future without leaving the past behind. “It struck me one day,” he said, “that perhaps I might utilize my scientific education to blend together science and romance into a work... that might appeal to the public taste.”

Just hanging out on the steps of La Maison de Jules Verne. Photo © C.W. Gross.

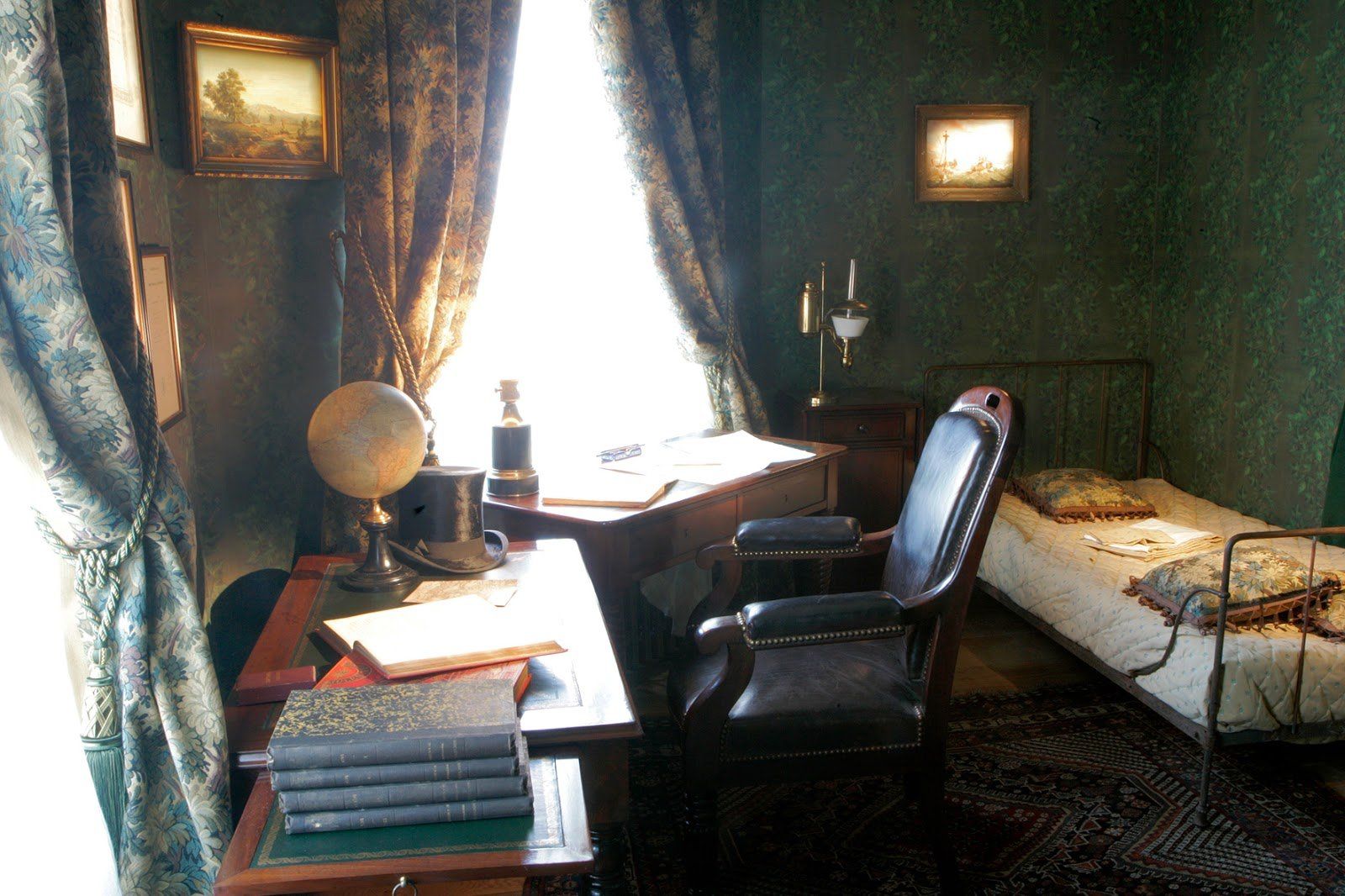

Verne's hallmark was meticulous research into the geographies and technologies of which he was writing. He became well-known at the local libraries, pouring over every available scrap of information recorded by explorers and colonizers. The author's regimen had him rise from slumber at 5:00 am and write for several hours before taking lunch and migrating to the public library to do research. Of his 54 Scientific Romances, approximately 26 were written at La Maison de Jules Verne. And of those, only the smallest fraction could be considered “science fiction” in the proper sense. The vast majority were adventure stories and historical novels that excited an increasingly literate public with faraway geographies and cultures. Even his science fiction novels are in this vein. How else to explore the ocean except by extrapolating existing submersible technologies? How else to explore the moon except by figuring out how to get there? How else to bring readers into the past except by having them literally descend through layers of geologic strata?

The study in which Verne wrote 26 of his novels. Photo © Laurent Rousselin – Amiens Métropole.}

The sense of wonder that revels in natural beauty and cultural diversity would be powerful in its own right. Yet this didacticism is not the only thing that makes Verne's work so appealing. Verne takes this further and studies the effect of these things on people. He projects not only invention or colonization, but what becomes of human beings in light of it. What matters in Around the World in Eighty Days is not as much the breakneck pace of the journey as how it opens the mind of Phileas Fogg. The Adventures of Captain Hatteras examines the effects of feverish obsession with conquering nature on the mind of the explorer. From the Earth to the Moon satirizes American affectations for grandiose projects. Twenty-Thousand Leagues and Master of the World ask what may happen if invincible technology gets in the hands of the vengeful or unscrupulous.

Jules Verne: A Literary Voyage is a three part series, written by C.W. Gross - Part One can be found here; Part Three coming soon!