C.W. Gross is the writer of the blog Voyages Extraordinaires: Scientific Romances in a Bygone Age and has recently published the anthologies Science Fiction of America's Gilded Age and Science Fiction of Antebellum America.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia - Part One

by C.W. Gross

Fantasia, released in 1940 as Disney's third animated feature, demonstrates everything an animated film can be. Across its seven distinct pieces, it proves that animation can be abstract (as in its Toccata and Fugue in D Minor segment) or narrative (as in The Sorcerer's Apprentice), mythological (Pastoral Symphony) or visualizations of scientific theories (Rite of Spring), comedy (Dance of the Hours) or horror (Night on Bald Mountain), anthropomorphism (Nutcracker Suite) or symbolism (Ave Maria). Married to the great compositions of classical music, it could also aspire to be high art. It is an incredibly rich, nuanced, and rewarding work, deeply rooted in the traditional fine arts... Far more than many would expect from a Disney film.

The physical storytelling in Fantasia is so accomplished that words were entirely unnecessary. No narrator was required to tell us that The Nutcracker Suite transitions through the seasons, and Mickey Mouse has no need to crack wise. What could Chernabog possibly say to make him more frightening? What could a David Attenborough add to Rite of Spring that we could not see for ourselves in all its violence and terror and power? Wisely, music scholar and radio personality Deems Taylor reserved his live-action annotations for between the animated sequences. His sonorous voice (now lost behind a dubbing over by Corey Burton, made necessary by deterioration in the negative) only gives us a few notes in the way of introduction to add to our enjoyment of the piece, like one may find in the program of an evening at the local philharmonic. Fantasia is a tour de force of pantomime, a lasting tribute to the skill of the animator who must draw every glance and gesture.

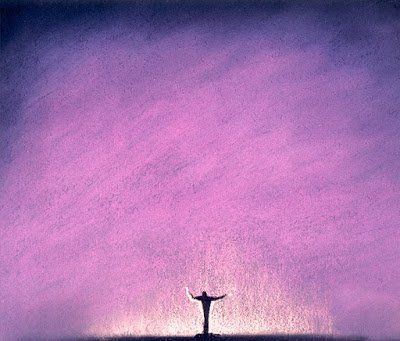

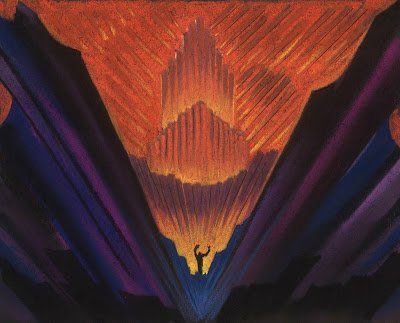

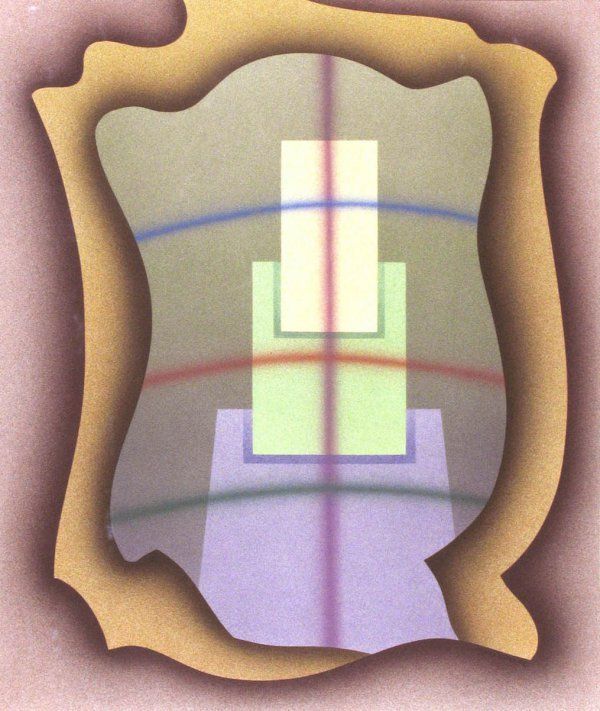

Concept painting for the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Photo © Disney.

Fantasia is artistically advanced but, structurally, comprised of short subjects recalling the "Silly Symphony" cartoons of Disney's past. A whole is affected, not through a coherent plot, but through the virtual experience of a concert performance. The opening piece, Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, calls attention to the orchestra and the instruments (through some brilliant lighting and editing). It also lulls viewers into a near meditative state. Fantasia's beginning is a liminal space, drawing the viewer out of the regular concerns of the world and beyond the mental space of seeking mere entertainment. That's one of the funny things about Fantasia: it's not really entertaining. At least not in the sense of being merely sensational or comedic or "fun" per se. It's much more than that. It is a film demanding attention in exchange for deep artistic gratification.

Toccata and Fugue in D Minor also introduces the viewer to Fantasia's distinctive but hard to trace visual style. It is painterly, yet lends itself so well to the sleek affectations of contemporaneous Art Deco and Streamline style. For many it seems to stand on its own, but its roots can be found deep within a short-lived artistic movement of the early 20th century, known as Transcendental Art.

Concept painting for the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Photo © Disney.

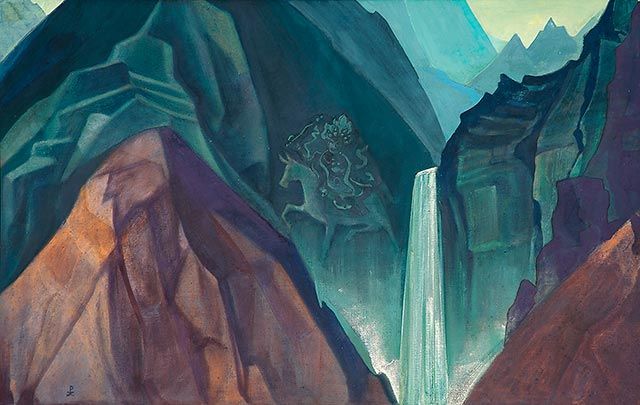

Born in 1872 in St. Petersburg, Russian painter and spiritualist Nicholas Roerich graduated from both St. Petersburg University and the Imperial Academy of Arts in 1893, with degrees in art and law. From 1906 to 1917 he served as the director of the school of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts. As many fashionable people of his time did, Roerich's attentions in the 1910's turned towards spiritualism, occultism, archaeology, Eastern mysticism, and the new religious movement called Theosophy. After the Bolshevik Revolution, the Roerich family migrated from Russia to Finland, then England, then the United States, and finally to India. An expedition spanning 1925 to 1929 took him and his family through India, the Punjab, Mongolia, Siberia, and Tibet.

Theosophy, an amalgamation of esoteric thought coalesced in 1875 with the founding of The Theosophical Society by Helena Blavatsky, holds to certain key principles about the nature of existence and human life in it. According to Blavatsky, it is "The substratum and basis of all the world-religions and philosophies, taught and practised since man became a thinking being. In its practical bearing, Theosophy is purely divine ethics." Which to more practical effect has three chief aims: "(1.) To form the nucleus of a Universal Brotherhood of Humanity without distinction of race, colour, or creed. (2.) To promote the study of Aryan and other Scriptures, of the World's religion and sciences, and to vindicate the importance of old Asiatic literature, namely, of the Brahmanical, Buddhist, and Zoroastrian philosophies. (3.) To investigate the hidden mysteries of Nature under every aspect possible, and the psychic and spiritual powers latent in man especially." By the last point, what is meant is that "We assert that the divine spark in man being one and identical in its essence with the Universal Spirit, our 'spiritual Self' is practically omniscient, but that it cannot manifest its knowledge owing to the impediments of matter."

For Theosophists and other esotericists, the imagination acted a crucial faculty in drawing mythic connections that excavated this deeper spiritual self. For Transcendental artists, that imagination manifested itself in a genre of painting that reached from stylized landscapes to pure abstraction, based in the worldview, symbolism, and numerology of Theosophy. Roerich's work is more literal in its depiction of places and people, but the simplification of detail in them hints to deeper underlying spiritual principles. Their simplicity leaves blank canvas for contemplation.

Left to right: Bridge of Glory, 1923. Palden Lhamo, 1931. Repentence, 1917. Star of the Morning, 1932

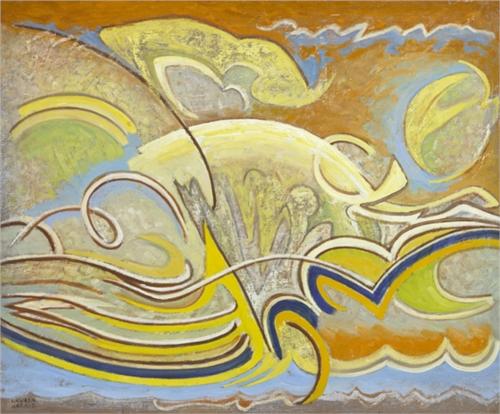

The banner of Transcendental Art was picked up in the United States by the Transcendental Painters Group, which formed in Taos, New Mexico in 1938. The goal of group founders Emil Bisttram and Raymond Jonson, as well as later joiners like Agnes Pelton and the Canadian expatriate and former landscape painter Lawren Harris, was "to carry painting beyond the appearance of the physical world... through new concepts of space, color, light and design, to imaginative worlds that are idealistic and spiritual." The Roerich gallery established in the Thirties in Santa Fe served as a regular gathering place for these artists dedicated to Theosophical ideas and artistic abstraction.

Left to right: Emil Bisttram, Oversoul, 1941. Raymond Jonson, Watercolor No. 23, 1940. Agnes Pelton, Spring Moon, 1942. Lawren Harris, Lake Superior, 1923. This landscape painting exemplifies his early work in Canada with the seminal national modern art collective called the Group of Seven.

Left to right: Lawren Harris, Abstraction 30, 1955. Concept painting for the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Photo © Disney.

Just as it is not overly difficult, I think, to catch similarities between Roerich (and Harris') landscape paintings to the landscapes of Fantasia's Rite of Spring, Sorcerer's Apprentice, Pastoral Symphony and Night on Bald Mountain, I also don't think it is difficult to see the trajectory from the Transcendental Painters Group to the animations of pioneer Oskar Fischinger. A presentation of Walther Ruttmann's Light-Play Opus No. 1 - an abstract animation set to live musical accompaniment - set Fischinger's brain ablaze with creative ideas. Like the Transcendentalists, Fischinger found inspiration in Buddhism, and particularly, spiritually rich and geometrically intricate mandalas. After fleeing Nazi Germany, Fischinger's experimental films landed him a position at Walt Disney Studios, where he worked on the original ideas for Fantasia's Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor. Unfortunately his ideas were too abstract, as Walt didn't feel that "little triangles and designs" was quite enough to sustain a big screen production, and Fischinger left without taking any credit in the finished production. Nevertheless, the echoes of Allegretto, An Optical Poem and Radio Dynamics (released after Fantasia) are still there.

On the Sublime and the Beautiful in Disney's Fantasia is a four-part series written by C.W. Gross. Part Two can be found here, Part Three can be found here, and Part Four can be found here.